I had written how Iranian women were struggling to reach out people behind the wall in the previous part of the Article. Infact, ,it is which side of the wall so as not important ,as long as the walls is in place, whether they are inside or outer side of the wall , the walls of the shade will be on their literary works. In this part of the article, I will give an ear to the voice of Iranian women outside the walls.

After the Iranian Islamic revolution, increasingly oppressive regime caused many Iranian women writers left Iran to continue writings in other countries. Almost all of these authors are anti-Islamic regime in politics. The vast majority of those women writers bring out sexuality and freedom of women in their work. The biggest aspiration in their country outside is to look after their mother language. On the one hand being away from their readers and live in different cultural environments, on the other hand is to stay away from the other dynamic of their mother languages are their common problems.

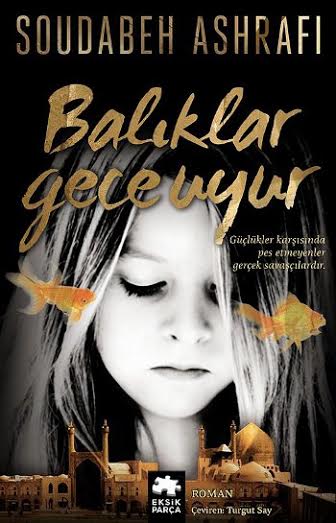

The most important Iranian women writers living abroad; Mahshid Amirshah (born in 1937 and lives in France), Goli Taragh (born in 1939, lives in France), Shahrnush Parsipur (born in 1946 will live in the US), Azar Nafisi (born in 1955 and lives in the US), Soudabeh Ashrafi (born in 1958 will live in the US). Unfortunately, among these writers, are only Soudabeh Ashrafi ( Fish Night Sleeping / translator: Turgut Say / Eksik Parça publications / 2015) translated into Turkish. Two important pieces of Amirshahi will be also available to read in Turkish in a year.

balıklargeceuyur

Soudabeh Ashrafi ‘s book ‘Fish Night Sleeping’ took place on the bookshelves in Turkish around 2-3 weeks ago . Thanks to my friend, Turgut Say who is the translator of the book, provided my contact with Soudabeh Ashrafi and I had the chance to make an interview.

Thanks to Soudabeh , I attempted to understand and increase my knowledge about how women writers living outside of Iran, affected the Iranian literature. Let’s see how we opened the doors of this mysterious world with this interview we will decide together now.

Soudabeh is 56 years old and lives for more than 3o years in California, in the United States. She is struggling to own her language, culture, literature from thousands of kilometers away. After the Revolution, during the hottest period of the Iran-Iraq war in December 1984 and she was forced to leave the country. She studied Journalism and Librarianship at the university. She is a mother with 2 children.

Has the Islamic revolution affected Iranian Literature?

The Islamic revolution has affected every aspect of Iranians’ lives; literature is no exception. 36 years of political and literary dictatorship continues to incapacitate the literary world in Iran generation after generation. The Islamic revolution has held individuality and writers’ creativity hostage. Living in a third world country with little to no human rights, one always watches what and how they write, despite their beliefs. During a period of political cleansing among intellectuals, writers, poets, free thinkers and elites, even translators and members of the Writers’ Association were murdered, imprisoned, kidnapped, silenced under house arrest, and banned from teaching. Teaching the works of many prominent writers and poets like Sadegh Hedayat, Ahmad Shamlou and Frough Farrokhzad, etc., who are considered the backbone of modern Iranian literature, is prohibited in universities. The permission to publish of many literary magazines has been revoked due to unapproved materials.

It goes without saying that a writer, in order to create and tell the truth, needs to have an individual mind separate from society’s influence and especially from the system that rules. This has not been possible in Iran. Iranian literature, fiction in particular, struggles with lack of freedom, true criticism and discussions. Writing is not valued as a profession. Writing may not be the most lucrative career in many countries but at least writers are free to express their mind as they wish and not be held accountable for it. The essentials for creating real literature do not exist in Iran; the world of writing has become depressed. There aren’t enough motivations for writers. The Islamic revolution has limited the value of literature unless it relates to Islamic values. The Writers’ Association is basically denounced and disabled. There are no conferences, no discussions, and no workshops—nothing to keep the flame of desire to create burning. There are economic obstacles too, such as a miserable book market and lack of enthusiastic readers (who can’t be blamed when good works are hard to find.) Many artists are forced to work mundane jobs to be able to survive.

How women writers did react against the Islamic revolution?

The lives of women writers were immensely affected by the Islamic revolution. Some left the country during or immediately after the revolution began. I guess they could sense the imminent upheaval and unrest. Some were unjustly arrested and imprisoned for years like Shahrnoush Parsipour. Some allowed their work to be censored and published, while others chose to remain silent. Those that couldn’t bare the censorship of their work chose to leave the country altogether when the opportunity arose. Nevertheless, despite the regime’s desire to silence their voices, a whole new generation of women writers is making a name for themselves in the fiction world. Though women have emerged from the chaos, there are still many challenges to be had in the literary hell of Iran.

Iranian women are brave and resilient. The writers among them are insistent on sharing their stories; they have maintained their curiosity, shed their dependency, and have crusaded for equality. This has not been easy in a conservative patriarchal society that wants women to sit silently confined within the walls of their house. However, from a literary point of view, they are gaining ground; it appears women writers are being published and read more than male writers in Iran. For whatever it’s worth, at the moment it seems that the market is better for women than men. Unfortunately there is still a long road ahead of Iranian women writers on the quest to equality and respect. Male or female, we as writers still haven’t achieved the goal of the “great modern novel,” which is individuality!

You have been living in USA for many years; do you think degree of homesickness prevents you from enjoying freedom?

I left Iran in 1985 and don’t think I opened my suitcases for a few years after that, waiting for things to change at home. I felt that my life outside of Iran was temporary, until it wasn’t anymore. After the Iran/Iraq war ended, there was a huge political and intellectual cleansing in 1989 and that’s when I finally lost hope. I went back in 1998 for a short visit and decided that the US was home. I would eventually get over my homesickness.

image

Can you explain your feelings as a writer out of your own country?

In 1990, I started to get serious about my writing. Because I write in Farsi, I don’t really have an audience here and it’s not a good feeling. Yes, I’m free to write my heart out but I’d like to publish and have a wider audience. It’s wonderful that writers can use the internet to self-publish and attract a larger community, but there is something to be said about having your work in a physical bookstore. I do feel a bit saddened because I am missing out on that experience. I don’t want to go through the censorship that my fellow writers do. However, I am very lucky that Fish Sleep at Night is published uncensored in Iran thanks to Morvarid Publishers. It garnered quite a bit of attention and won a few awards, but this has been the exception and not the rule for Iranian writers who publish outside of the county. I’ve even had a collection of my short stories get rejected and was forced to self-publish online.

I often don’t talk about my books and seldom introduce myself as a writer here, since I don’t have much to show in English. I have been published in English here and there, but not enough. I’d like to be recognized as a writer, but the market here is challenging for Middle Easterners even if I wrote in English.

As an Iranian women writer who is living in America, how do you think your writing has been impacted?

Living here has given me a chance to read the masters directly and not through translations. That’s actually how I learned to write short stories. I’ve been able to live among the characters they described. I’ve learned to try to look for my own identity as a woman, to be an individual and speak my own true mind. It has helped with the struggle of finding my own voice. I’m still an Iranian woman, even as a writer. The memory bank, the language bank, and the upbringing– I still carry them all within me. I still have to learn how to let go of all those things and write about taboos, banned and prohibited issues. Living here has taught me to get rid of all the eyes watching me—the patriarchal father/brother eyes. On the other hand, living in America (where one has to work hard for a living) has also impacted my writing. Trying to make ends meet puts writing on the back burner!

Can you please explain little bit about Iranian literature? Specific characteristics of Iranian modern literature?

Talking about modern Iranian literature is a daunting task. It is difficult to distinguish the many characteristics of Iranian literature, like you can in American literature for example. Modern Iranian literature especially short stories and poetry flourished during 1950s which was considered to be the best era of Iranian literature. However, there has always been a struggle between the government and the literature. Before the revolution, under the influence of Soviet Union politics and novels, many authors employed Social Realism in their writings against the monarchy. In order to be considered a great writer authors had to incorporate politics in their narratives. Doing so made one appear intellectual regardless of actual intelligence, knowledge of politics or the literary value of one’s work. Authorship and intellectualism were intertwined and confused. I think fiction in general was mostly political.

The Iranian literature, since the 1979 revolution to present, has not been as dynamic nor gone through completely different turn. Many writers emerged, and numerous novels and short stories have been written and published. Nevertheless, not too many have been able to freely cover the characteristics of modern fiction such as peoples’ lives, history, sexual diversity, women issues, societal critiques, personal experiences and opinions. Even the most successful novels have gone under the knife of censorship. Many were published and, distributed and swiftly taken off the market due to the use of forbidden materials or even words, by the Ershad, Ministry of Islamic Guidance. The Islamic republic lives on an ongoing revolution on every aspect, they expect all Iranians on every level, poets, writers, artist to respect the Islamic ideology and stay within the boundaries of Islamic values. This expectation is allowing the establishment to order and control the art and literature beyond imagination. Therefore, I believe that Iranian literature, particularly the novel, has been stifled under these harsh circumstances.

There have been at least two major historical events that have changed and devastated the country and are worth writing about. First the Iran/Iraq war, and second, the cleansing of political opposition and intellectuals. People’s lives have been touched and changed because of them and their actions. One would think that one should be able to explore the lives affected, through literature. But, not too many writers have touched the issues in their writing due to their fear of being censored, rejected by publishers or even arrested for that matter. And if they have written any, publishers have refused to touch them. Instead writers have focused on forms and techniques, rather than ideas or have just written light stories within the frame of the government’s acceptance. Although that there have been quite a few worthy novels written outside of the wall of Iran, narrating the untold stories of those who live within the country itself. And some inside, escaping the censorship by chance.

What inspired you to write “Fish sleep at the night”?

A true story that I heard was the inspiration. That story actually was about a “lost brother” who had done something similar as in my story. I started imagining the changes in a family when something like that happens to it. What will they do? Will they forgive? That was my main question. Then came, Fish Sleep at Night.

Did you try to sit on the other side of the table with your readers? What do you think about your books ?

I do that all the time after a work is finished. I think my book touched a lot of readers. Many had identified their family members with the characters. Women especially made a connection with Talayeh and her mother.

Do you know Turkish modern novel writers? What do you think about Turkish modern literature?

Not a stranger. I’ve read Aziz Nesin as a child and Yashar Kemal as an adolescent. I’m familiar with and love Nazem Hekmat’s poetry. Reading Pamuk is a joy. I’m glad that Turkish literature has found its place in the World

I have a blog and I have mainly writing on diversity and women issues. What do you think about on this matter? Could you please tell us something on this matter?

Women are and will be an ongoing issue all over the world, always. Especially with the Middle East crisis these days. Women have to be the topic of everybody’s social life. I’m glad that the world is now seeing more of what is happening in other women’s life around the world and in the horrible patriotic and religious societies. More Power to you and let’s not stop!